My favorite part of reading a work of science fiction for the first time, like visiting a new country, is that hit of strangeness, of being someplace where I don’t know the rules, where even the familiar is unsettling, where I see everything with new eyes.

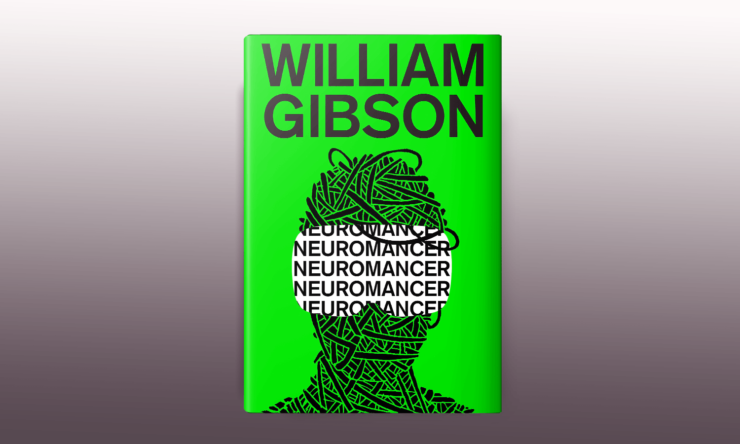

In 1984, Neuromancer delivered that to me. I read the book in small bites, like one of those sea-salt caramels that are too big and intense and salty to consume all at once. The first few chapters are especially chewy: I like the almost-brutal profligacy of the prose, new words and ideas cascading out of the book fresh and cold as a mountain torrent, and be damned if you lose your footing. The opening vision of an assaultive future is wide-ranging and obsessive, as if the narrator, dex-driven and frantic in Chiba City, just can’t turn his consciousness off. Everything he sees has layers of meaning and speaks of the past, the present, and the future all at once.

There’s not a wasted word in these chapters, and now, nearly forty years later, if any allusions escape the hapless reader, cyberspace is here to help. In 1984, if you didn’t know what a sarariman was, no dictionary did either. Now you can just google it. We all speak a little Japanese now, and we know our way around Chiba City, at least in our heads. We’re comfortable in cyberspace, though our cyberspace looks a bit different than Case’s. Twenty-first-century readers, no longer tourists in this future, pretty much know where they’re going, and that means they can keep their balance, negotiate the intricate thriller-dance of the story, and examine the larger themes against which it unfolds.

William Gibson’s cool, collected language doesn’t make a big deal about this being the future. Your brain glides smoothly past quotidian details that might have been futuristic the first time you read them, but now are just the way the world rolls. The transition to global connectedness and a global economy has been accomplished; cyberspace is here and people all over the world have casual access to it; outer space is an international arena and not just a US/Soviet hegemony. There are Russians here, or, at least, the clunky remains of their materiel, but, presciently, there are no Soviets in Neuromancer.

Gibson has a talent, evident in all his novels and stories, for observing and analyzing the strangeness of the life around us. He writes on the bleeding edge of everything he observes–– technology, politics, human society and consciousness––and he extrapolates beyond that edge into a future created from observation of our own time, so the path to that future is strange but intelligible. There’s a moment, every now and then, when the extrapolative curtain slips to show the clockwork, but the glitch barely registers. A bank of payphones rings in a hotel lobby, and the game is briskly afoot.

What is most interesting about Neuromancer is not the caper––although that’s certainly intricate and interesting itself. It’s not simply the suggestion of a compelling future––some of which has vanished from the text merely by coming to pass, but much of which is intact and captivating. What is most interesting to me, after forty years and many re-readings, is its meditation on the relationship between personality and memory and humanity, on originality and creativity, on what makes people real.

***

At this point, if you’ve never read Neuromancer, or if you don’t recall the plot, you might want to go read the book before continuing to read, here: I sense spoilers creeping inevitably into my text.

If you are re-reading Neuromancer, keep an eye on the characters and how they are who they are. For many of them, what they do is their entire identity. At the beginning of the book, Case is subconsciously suicidal due to the loss of his ability to plunder heavily guarded cyberspace databanks. What he does is who he is, and he can’t do it any more. He’s suffering from miscreant’s block: an inability to do the crimes he likes best.

Molly, from the very beginning, identifies herself closely with her bionically amplified ferocity and hyperawareness of danger, her synthetic muscles and implanted weaponry. None of it is particularly natural, but, right to the very end of the book, she is wedded to the idea that these characteristics are intrinsically part of her “nature.”

Stream-lined, blank-faced Armitage, an apparent construct who recruits Case for an unknown employer, triggers Case’s uncanny-valley reaction––this despite the fact that ordinary people in this future routinely rebuild their faces in ways that mask their emotions and individuality, like so many Botoxed supermodels. However, there is something transcendently off-putting to Case about Armitage’s personality…

Case’s cyberspace mentor, the Dixie Flatline, dies before the beginning of the book. A recorded construct of his memory and personality, revived after Dixie’s death, displays the dead man’s skills and obsessions, even his conversation patterns, and continues to advise Case. It sounds like Dixie, it knows what Dixie knew, it can give Case pointers on how to crack black ice, but it’s flatter than the Flatline himself, and it’s painfully aware that it is an unconvincing imitation of its own personality. Like Armitage, the Dixie construct is a sort of zombie: death gives neither of them release.

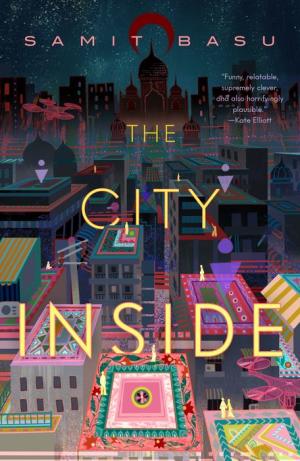

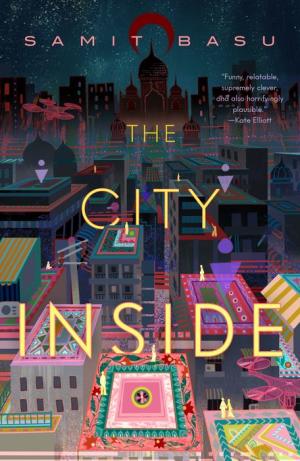

Buy the Book

The City Inside

In addition to considering personality and identity, life and death, the story explores the possibilities of intelligences without bodies and bodies without intelligence. Molly tells Case about her time as a meat puppet, renting her body out for the sexual pleasure of others while temporarily disconnecting her mind. Armitage is also a kind of meat puppet, and the Dixie construct is an inversion, a self-aware non-meat puppet.

As Case and Molly get closer to finding out who is employing them and why, the question grows of what constitutes a person, and whether personality and ability have any relevance in a world in which everyone, for a price, can enhance themselves surgically, intellectually, and chemically. People can have their faces rebuilt to render their thoughts impenetrable or to present an off-puttingly ugly visage. They can plug silicon shards into their skulls for access to knowledge and skills that used to require decades of hard work. They can access exquisitely precise designer drugs.

In the latter part of the novel, the issues of human versus artificial intelligence, of what machine intelligence wants and what it will do to get it, become more important. If machines can appear to be human, does that make them so? What is the difference between humans and simulated humans? What would it take to make an entity that is more than human, rather than an imitation? And would such a being have any resemblance at all to humans, or any need for humanity?

The question of whether artificial intelligence can supplement human intelligence takes a quick left turn and becomes a matter of AIs breaking the bonds that connect them to humans and looking elsewhere for intellectual companionship. At the end of Neuromancer, after you, the reader, have been tossed six ways from Sunday, Wintermute and Neuromancer have their own say about memory and the mind, as they contemplate the death of their separate selves in the birth of a larger consciousness.

***

Fiction, even science fiction, is not about the future: I think everybody knows that. So what is the “future” that Gibson describes here? It’s a future that in some ways looks remarkably like the present: the US hegemony is fading, the poor have gotten even poorer than they were in 1984, and the truly rich have power that the rest of us can’t even imagine. Although often described as glorifying computer programmers as a cohort of romantically wild console cowboys, Neuromancer pushes back at the idea that technical advance always results in progress. This book is still surprising, still relevant, and it still deals with unanswered questions.

The book paints a world in which humanity is divided into the superrich, a middle class of salarymen, and a huge proletariat of the desperately poor who have been denied meaningful employment and have their own economy of graft and blackmail. Most of the characters in Neuromancer are struggling to get by any way they can. Case bought his enhanced data storage, Molly bought her mirrorshades and muscle and blades. Their purchased enhancements make them useful to crime syndicates, but do not offer tickets out of the Sprawl.

Gibson pays attention to––and calls the reader’s attention to––the touch and feel of life in the Sprawl, even in the grungy elevator of a cheap coffin hotel, and uses the detail to create emotional weight: “The elevator smelled of perfume and cigarettes; the sides of the cage were scratched and thumb-smudged.” The politics of the Sprawl are drawn from the smudges and smells of people living in the grime of poverty.

What we’ve come to experience more fully, in the years since Neuromancer was written, and especially since the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, is the internationalization of information and cultural life. So much of life takes place on the Internet now, and even with the restrictions of certain nations’ firewalls—China’s and Russia’s in particular—information and cultural communication move globally in a way that Neuromancer only hints at. It’s hard for me to remember what life was like without Zoom, let alone without email and message apps and social media, without cell phones, without the whole world crowding unimpeded into my consciousness, 24/7.

In Neuromancer, the United States is a relatively unimportant country, and Japan and China are on the cutting edge of technology and medical research. The book’s depiction of international commerce, in which megacorporations, zaibatsu, and criminal enterprises rule the global economy, was not consensus public opinion in the English-speaking world in the 1980s, although the transition to the reality we have now was well underway. The idea that street criminals would dip with impunity into the data strongholds of governments and corporations and render them helpless—or hold them hostage—seemed impossible, because governments and businesses stored their most important data on little pieces of paper, so tedious to search and cumbersome to copy. All these things, part of our consensus reality, are not science-fictional now: they form the reality-based background of the story. The possibility that life in a space station could be commodified into a low-orbit Ibiza, with just a frisson of gravitational confusion, really doesn’t seem quite so strange today.

Gibson himself has said that, in creating a future that didn’t end in a global nuclear disaster, he thought he was creating an optimistic future. In the 1980s, reading Neuromancer’s grim future somehow alleviated, for me at least, the fear that the unknown future would be unsurvivable. It made today a familiar place. Our fears are different now, but Gibson’s books continue to serve that purpose.

***

The essence of Gibson’s writing is its combination of clarity and allusion: the precision of the details he gives and their perfect congruence with the emotional and political tone of the story. As is all of Gibson’s work, Neuromancer is a book of exquisitely observed detail that moves back and forth through time. I am especially fond of the description, near the beginning of the book, of Japanese street vendors selling blue koi in tanks and bamboo cages of mantises and crickets, the ghost of old Edo inside the shell of future Tokyo.

Neuromancer does more than examine the years in which it was written, the early 1980s. It provides readers—and even people who have never read it—with ways of thinking about the technological and economic transitions of the past fifty years, the evolution of how we store memories and data, and perhaps about the ways in which employment and bodily autonomy are related. Much of Gibson’s work––his short stories and his three novel sequences––is concerned in some way with the interplay of intelligence and memory, and the relationship between rich and poor. It is imbued with an odd kind of optimism about the future: as bad as it gets, he says, someone will survive. And the poor we will always have with us.

I first read William Gibson’s work in manuscript, before his first professional publication, before there were any actual cyberpunks. It woke me from the writing doldrums I had fallen into. His language, like Faulkner’s, made me dizzy with envy. I had to go over a story three times before I had any idea what the crux of the action was, but I knew that this was what would make science fiction interesting to me again. His choice of subject matter told me I didn’t have to write space operas, his style that I didn’t have to worry whether readers would understand my allusions. I didn’t have to mask my politics or constrain my imagination or write conventional novels of character. His first few stories told me I could write anything I wanted, and that it was my job to do so.

At the same time, I was pretty sure that the general science-fiction reader was not ready for either the politics or the prose. I thought, “It’s a shame that this poor bastard will spend the rest of his life writing in total obscurity for pennies a word.” So much for my powers of prognostication. My opinion of humanity has been elevated, and I am so happy not to be living in that particular parallel universe.

I urge you to read and re-read not only Neuromancer, but Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive, the subsequent books in the Sprawl trilogy. As Gibson continued to explore this alternate future, he continued to extend his mastery of craft and content. In the two following books, his larger vision of what he was writing about becomes evident, as I think it did to him as he wrote them. The Gibsonian world and the Gibsonian universe are larger and more diverse than Neuromancer, larger even than this entire trilogy. They contain multitudes. If you don’t already know them, I hope you will check them all out. His peculiar dystopian optimism, that humans will somehow elude complete obliteration, has grown larger over the years, and we need it more than ever.

Note: “Does the Edge Still Bleed?” was written as the introduction to a new edition of Neuromancer, to be published in the summer of 2022 by Centipede Press.

Eileen Gunn is an American science fiction writer and editor. She is the author of a relatively small but distinguished body of short fiction published over the last four decades. Her story “Coming to Terms” won the Nebula Award in 2004 and the Sense of Gender award in Japan in 2007. Other work has been nominated for the Hugo, Nebula, Philip K. Dick, Locus, and Tiptree awards. She has two volumes of collected work, Stable Strategies and Others (Tachyon Publications, 2004) and Questionable Practices (Small Beer Press, 2014), with a third, Night Shift, due out from PM Press in June, 2022, as part of their Outspoken Authors series. She was editor and publisher of the pioneering webzine The Infinite Matrix and creator of the website The Difference Dictionary, a concordance to The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling. A graduate of the Clarion Writer’s Workshop, Gunn served for twenty-two years on the board of Clarion West, and is currently on the board of the Locus Foundation. She has taught a number of workshops at Clarion West and at Seattle’s Hugo House, both online and in person. Gunn also had an extensive career in technology advertising, including a stint as Director of Advertising at Microsoft, and says she knows more about the history of computing than is either reasonable or polite.

Great analysis, Eileen. I’ve read all of Gibson’s work and am impressed at how consistent he is: He had that unique writing style and perspective right from the beginning, and has applied it to various near-future scenarios and topics through the decades.

His recent books may not dazzle everyone quite the way Neuromancer did, but that’s because the field has become accustomed to his voice and style. The time-travel twists and autonomous AI in “The Peripheral” and “Agency” show that the master can come up with new variations on classic themes. Write on, Mr. G.

In my mind, Gibson was great at the start, flying blind on technology, but a great stylist. Comparatively, Stephenson’s Snow Crash was very self-aware (and less tech-noob). He’s gotten better: The Peripheral and Agency are amazing novels (surprisingly not nominated for Hugos), the Blue Ant trilogy might be my favorites. But he always surprises with an odd way to apply technology, to push past the reasonable into the fantastic — The Peripheral’s use of cheap remote labor workers in the alternate reality (or is it a simulation?), Agency’s self-emergent AI having subconscious subroutines of which it is not aware.

He remains a stylist — the prose is at least as important as the plot (and yet I’m a fan of the PJF), but also one of the few people able to write characters smarter than the audience.

This is a very accurate assessment of why the trilogy works. And my first reading of it would exactly echo the author’s. But my second reading of it (some thirty years later) was a rather different experience, thanks to that disorientating mixture of what Gibson got right and what he got wrong (those phones, in particular). Back then I knew I was reading about a possible near-future. What was I reading in 2014? I couldn’t say.

I once read a description of Neuromancer‘s world as one ruled by MBas (this was written by an engineer), something that’s always stuck with me.

Another feature of Gibson’s work is his attention to style (clothing, hair, furnishings etc.) and how it defines us.

Grrat read! One small comment: It seems every Neuromancer piece out there references (typically negatively) the pay phone “scene”. And not without merit as WG’s famously said the advent of smart phones is the biggest miss of his projection of the future.

But when it happens in the book, it’s absolutely arresting for Case and the reader. Even 40 years later it’s magnificently cinematic. The absurdly powerful computing power/intelligence/connectivity it would take to 1) Observe Case walk through the station 2) Calculate his pace so that each call/ring perfectly matches his gait 3) Not only time/choreograph everything but connect to each phone to initiate the ring…

Pulling off all of that in real time is an incredibly cinematic sequence that would have awed the character (and maybe convince him of the authenticity of the reward) and of course also the reader/audience.

There’s a similar scene (this time it really was actually filmed not just playing in my head) at a press conference in the BBC’s “Sherlock” series that involves text messages and it works there too.

To be fair, NervusVaron, your four paragraphs say the same thing I said in my essay in 19 words: “…the glitch barely registers. A bank of payphones rings in a hotel lobby, and the game is briskly afoot.” That was my experience–the pace is fast, no time to waste on minor points–and I’m glad yours was the same. Not everyone’s will be, but that’s okay too.

As a youth on an Indian reservation, sci-fi was the ultimate escape not just from my home, my town but the world in ways beyond my at-the-time limited imagination. I lost that in adulthood until a friend said ” You read a lot ,try this.” & handed me his copy of Neuromancer. He had the first 5-6 of Gibson’s novels , it took me less than a week to consume all. I keep all his novels on my Kindle, un-ironically, with what others regard as classics. Connelly, Christie,Doyle, Verne & Gibson. William Gibson’s novels rekindled my appreciation for sci-fi & a nostalgia for the future I enjoyed as a child. I recently recalled a portion of a story I was fascinated with, Googled it. Isaac Asimov’s ” It’s such a beautiful day.” The idea of “googling”(“Lougle” if you’re a fan of ” Hot Tub Time Machine”)in 2022 a story from the 1950’s that you read in the 1970’s about something in the future,doesn’t that sound like science fiction?

I’ll never forget the day, as a kid, when I first read WG’s brilliant short story “Hinterlands’ in the debut issue of Omni magazine. Few other stories, short or long, hit home so hard describing the insanity that will afflict our little tree dwelling simian brains out in deep space. I was hooked! His short collection “Burning Chrome” is one of my faves. I also really like the Neuro follow ons, esp “Count Zero”. The “Bridge” trilogy was okay, but nothing hit as hard as the Sprawl trilogy and the short collection. Gibson managed to help form the forward thinking mindset of an entire generation.

For another short with that “Hinterlands” feel, go read the short “Beyond the Aquila Rift” by Alastair Reynolds. Also brilliant.

“Hinterlands” was published in OMNI’s October 1981 issue. OMNI’s debut issue was published October 1978.

“Neuromancer” to me was one of those works that divide the world into a before and an after.

The ways in which he got the present right are amazing, the answers to the question of what it means to be human even more so.

For me, one of the most arresting elements of the Sprawl trilogy was that when the AIs fuse they don’t manifest as some megabrain Hal type thing, but use the Loa as templates which trips the whole story into an utterly new path. You can tell Gibson is an avid Fortean Times reader!

Neuromancer remains my favorite science fiction work. There’s no doubt that some aspects of it feel dated (Gibson was writing about the future from the perspective of the early 80s, after all) but as this author so aptly points out, so many elements of the book still resonate with us today. And of course it’s just a fantastic neo-noir story on its own merits.

I’ve read all of Gibson’s works of course, but I believe The Peripheral is his best since Neuromancer. I’ve probably read it 5 or 6 times. I suspect in the coming years and decades we’ll see more than a few references to “the Jackpot.”

As recently as my last trip to Japan 3 years ago, there were still pay phones all over the place, including banks of them in western-style hotels and train stations. There are apparently still lots of older Japanese folks who have no cellphone at all, and many others still have “feature phones”, basically flip phones with better cameras and games. As late as 5 years ago, the Japanese government was still making it difficult to get a domestic phone contract (even pre-paid) without a permanent Japanese address. If I needed a phone or data modem, I’d order it from a company in Taiwan who’d ship it for pickup at a specific post office at the arrival airport, included in the package would be a postage-paid envelope to mail it back at the end of the trip.

I might add that the sky can still be the color of a dead television; only bright blue, now.

Not to draw out the cell-phone discussion, but it occurs to me that, since instant communicators were such a sci-fi thing in the previous 3 decades, Gibson may well have resisted, consciously or un, using that device in Neuromancer. (I have never heard him say any such thing, btw. This is pure speculation on my part.)